Exploring Cuba

There were many things that surprised me on my first trip to Cuba, when we traveled with the volleyball national team for a series of friendly matches. But beyond playing against a world volleyball powerhouse (at that time), and traveling without my parents for the first time (I was 12), what I enjoyed the most about the trip was getting to know Lázaro.

Lázaro Alzugaray was one of the referees in the tournament. He was around 65 years old, a skinny man with sun-toasted skin. After each game, our coach's instructions were for us to sit in the stands and analyze the strengths and weaknesses of the other players and teams. But by chance, I sat next to Lázaro, who was on his break. For the next few days, we talked for hours (and not precisely about volleyball). He told me what it was like living in Cuba, described the island with all its lights and shadows, and usually lowered his voice when referring to the government.

I felt like an undercover secret agent collecting important information about a place I knew so little. And I loved it.

Learning from Lázaro made me realize that I wanted more of that: I wanted to learn from other countries and their people and their stories. I wanted to ask questions. To explore places…

We talked every day after each match. The coach never said anything, maybe he thought I was asking the referee what makes cuban volleyballers so good…

At the end of the tournament’s last match, Lázaro gave me a book, Cien Horas con Fidel, which includes long conversations held between Fidel Castro and the French journalist Ignacio Ramonet between early 2003 and mid-2005. “Read this to continue learning and questioning. Become an explorer of the world”, Lázaro said.

When my parents asked me how my first experience playing abroad with the volleyball national team was, I excitedly replied that it was great. That I had figured out what I wanted to be when I grew up. A professional athlete?, they asked, hesitant. No, I said. I wanted to be a journalist.

This little moment in my life’s journey was crucial for me, because it sparked a desire to become an explorer of the world. Volleyball had its expiration date (even though I kept playing for 10 years after that first trip to Cuba), but the curiosity that was awakened with those conversations with Lázaro... that curiosity has only grown more and more with the years.

Discovery Projects

Becoming a journalist didn't work out. I learned in my first year of college that it was one of the most dangerous professions in my country (I had to experience it myself, despite my parents' warnings).

But I discovered a common thread in many of the projects I was part of. My first blog (which I was surprised to find still alive in the sea of the Internet) was called “Navegante” (Navigator).

When I was asked to co-organize a TEDx event at my university, I made a convincing pitch to theme it on maps and exploration. The event was called 'Mind the Map: Exploration and Discovery' (here I am, rather enthusiastically, talking about the event at 0.27).

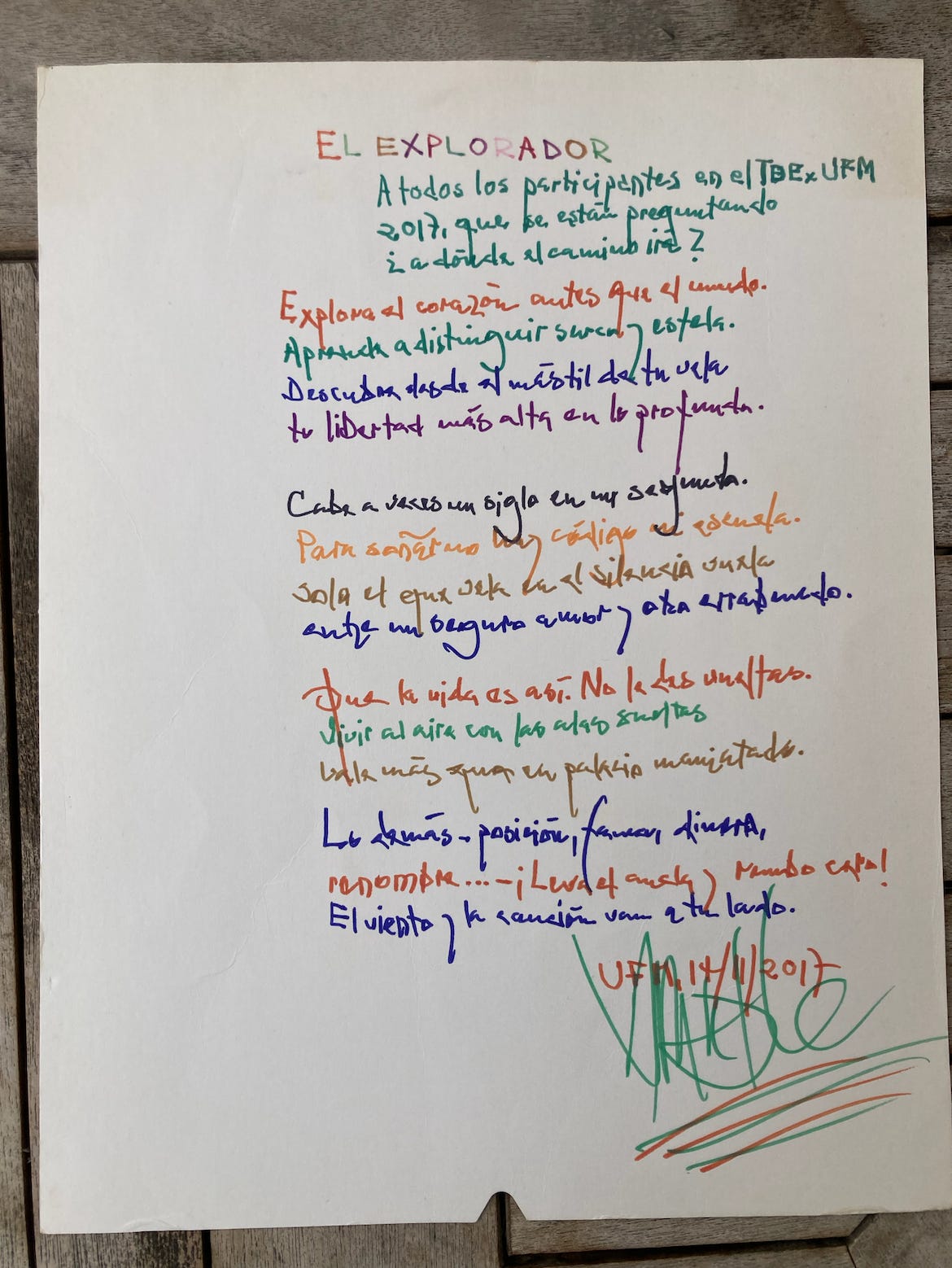

Amable Sánchez, a master of the sonnet whom I deeply admire, even agreed to write a poem to the TEDx participants. It’s called: “El Explorador”.

Explora el corazón antes que el mundo

aprende a distinguir surco y estela

descubre desde el mástil de tu vela

tu libertad más alta en lo profundo…

And here’s the English translation:

Explore the heart before the world,

Learn to distinguish furrow from wake,

Discover from the mast of your sail,

Your highest freedom in the depths below…

My first book, published in my early 20s, is called “La Odisea del Atlántico”, (The Odyssey of the Atlantic), and it tells the story of a prisoner who ends up on a ship. The book is a fictional account of the first voyage to America told not from the eyes of renowned captains and experienced sailors, but from a timid guy full of questions and a longing for adventure.

A few years later, I wrote “Lola la Ola” (Lola the Wave) for a Children's Literature contest (which I never heard back from). The little book was the story of a wave that wanted to break the rules and set off to explore and discover other seas...

My 20s were marked by decisions that maximized my range of exploration: I wanted to learn to program to learn how to build worlds with words. I made more than 20 trips with the volleyball team. I lived a few seasons in Austin and Chile.

I’ve always wanted to be an explorer; to have the privilege to discover something new. But I grew up thinking that to become a proper explorer I needed to become someone else: someone agile, fast, someone who thinks on her feet… I thought discovering something unique was correlated with how fast you managed to get there (or in other words: if you managed to get there first).

But, what really makes for a good explorer?

Volta do mar

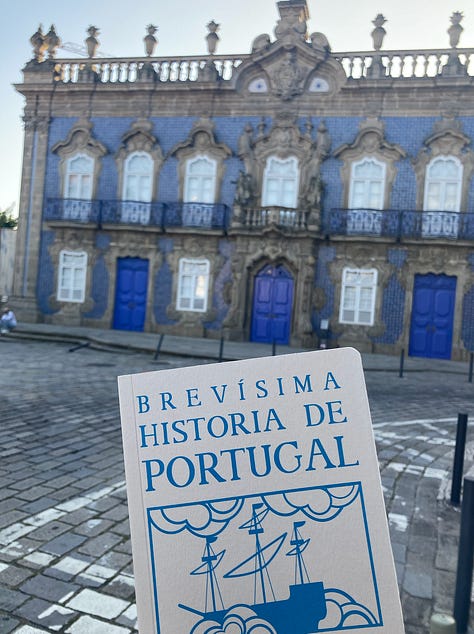

It’s probably not a coincidence that of all places, Fer and I have been living in Portugal in the last few months. For me, it’s been a convenient gateway to learn more about some renowned (actual) explorers: Prince Henry the Navigator, Vasco da Gama, Ferdinand Magellan, Vicente Pinzón, Pedro Álvarez Cabral… all instrumental in expanding Portuguese influence, establishing trade routes, and contributing to the Age of Discovery.

While learning about sailors and voyages, one particular expedition stood out. According to historian Roger Crowley, it was to prove one of the most significant expeditions in the history of exploration, but also one of the most mysterious. It went almost unnoticed in contemporary records, as if Portuguese chroniclers were looking the other way…

At that time in Europe, nobody had the knowledge of navigating the Atlantic. Prince João, Henry the Navigator’s great-nephew, was preoccupied with the “deep desire to do great things”, the first of those being the exploration of Africa.

In 1486, João appointed a knight of his household, Bartolomeu Dias, to command the next expedition down the African coast. A year later, Bartolomeu Dias and his little flotilla sailed out of the Tejo. They had been at sea for months, zig-zagging and facing difficulties to come back due to the prevailing winds and ocean currents. Because of the structure of the Earth, winds blow from the Sahara towards the Atlantic Ocean, slightly southwards. Ships that sailed from Europe down the Sahara coast had to go back upwind, all while pushing against the sea currents1.

In the middle of this struggle, the pilots gave up the battle with the winds and currents and took a startling decision: they turned their ships away from the shore, lowered their sails to half-mast, and flung themselves out into the void of the westerly ocean with the counter-intuitive aim of sailing east. For thirteen days and nearly a thousand miles, the half-masted caravels ventured out into nothingness. There, they picked up westerly winds that carried them east back to Portugal.

They termed this strategy “volta do mar”, or the "turn of the sea", and it was a decisive moment in the history of the world. The culmination of sixty years of effort by Portuguese sailors...

The battered caravels re-entered the Tejo in December, 1488. Dias had been away sixteen months, discovered 1260 miles of new coast, and rounded Africa for the first time.

For the Portuguese, the swiftest route back home from Africa wasn't a direct path to Portugal, but rather an initial push further into the ocean…

Go slow to go fast

Finding the tip of Africa and reaching the Indies was the beginning of the Portuguese Empire. The Portuguese were well positioned and fast, but that’s because by the end of the 1400s, they understood the currents and winds of the Atlantic so well that they realized they could do a volta do mar in the South Atlantic. It was during one of these volta do mar that the they discovered Brazil).

In my original definition of what it means to be an explorer, I thought that being agile and fast were key characteristics (a fast learner, an agile entrepreneur…) What the Portuguese’s Volta do Mar taught me is that sometimes to go fast, you need to go slow. They took a counterintuitive decision, flunked themselves into uncertainty, and traveled the longer path. Instead of applying brute force to navigate against the winds and ocean currents, they took a completely different path altogether.

These ways of working with problems, going fast or slow, can be seen in all domains. In one of my favorite Substacks, Henrick Karlsson describes how mathematician Alexander Grothendieck wrote about two opposing strategies when confronting problems: 1) “attacking the problem”, which is essentially trying and failing until the problem, through sheer force, cracks open; and 2) exploring the problem in an open-ended way, being willing to spend a long time in it and building intuition as you go.

My co-founder and I have talked about this before in the context of our company, TeamLogiQ. I like how he’s defined it.

Here are some other thoughts on going slow to go fast:

Henry David Thoreau, in his journal entry for November 5, 1860:

I am struck by the fact that the more slowly trees grow at first, the sounder they are at the core, and I think that the same is true of human beings. We do not wish to see children precocious, making great strides in their early years like sprouts, producing a soft and perishable timber, but better if they expand slowly at first, as if contending with difficulties, and so are solidified and perfected.

Idler editor Tom Hodgkinson and a group of around 15 authors, artists, and teachers came up with a “Manifesto for Slow Learning”, which includes a “Bill of Rights” for the slow learner. Here are three of those ideas:

Learn at your own pace

Find your rhythm, find your flow. Don’t compare yourself to others.Unlearn and forget

Harness the power of unlearning. Reboot your mind, abandon old knowledge, actions and behaviours to create space.Slow down

Sometimes slow and steady will win the learning race. Make haste slowly.

The fish analogy

Last week, on a walk to Foz along the riverbank that later becomes the sea, Fer and I were talking about paces and rhythms, and he came up with a brilliant analogy. “How many fisherman have you seen in our walk today?”, he asked. “Around 60”. “And how many fish?”

I realized we’ve only seen one.

It takes time to catch a fish. Most of the time, we pull out the rod before it bites. How do we know how long to wait? How can we tell if there are fewer fish today and maybe it's better to give up fishing, or if we just need to be a little more patient? And even if we wait long enough, there’s no guarantee that we’ll catch a fish.

In the context of entrepreneurship, Hugo (again very wisely), once told me that starting and running a business takes three things: patience, perseverance, and faith (see: The Tortoise and the Hare). It’s worth optimizing for long term wins.

I smile when I remember that first trip to Cuba, and the firm resolution I had to become an explorer of the world (whatever that meant). But aren’t we all explorers, after all? Fisherman on the shore, waiting to catch a special fish?

You don’t need to go faster to get further.

If you already are a curious person, all it takes is a little patience, perseverance, and faith.

At times, you must summon the courage to swim against the current, said Bruno. It may not be the most apparent choice, nor the one favored by the majority. But remaining true to yourself and your ideas is a pursuit of genuine worth. — La Odisea del Atlántico

Just for fun

I bet this is how finding new routes and lands most have felt like.

🌀 Rabbit Holes

The Ages of Exploration (a few interactive maps)

A wonderful unfolding of an idea. Muchas gracias!