For a carnival dance, I wore goalie gloves, a goalie jersey, and goalie knee pads. Nevertheless, on the street, a girl stopped me to ask what I was dressed up as.

My best friend from school was named Néstor Frenkel.

Néstor Frenkel’s father had a Ford Fairlane.

Néstor Frenkel’s phone number was 783-0448.

The pen I used at the David Wolfsohn School was an Astor 303.

I asked my parents for a Parker. It was the one almost all my classmates used.

They bought me a Sheaffer.

These memories come from LS83, the surprise film at this year’s Buenos Aires Independent Film Festival (BAFICI).

As the lights dimmed in the movie theater, Martín Kohan’s voice began narrating more excerpts from Me acuerdo (I Remember), memories from his 1970s childhood in Argentina. Meanwhile, the screen filled with archival Channel 9 news footage that had never been made public until now.

The result was a documentary that weaves together Kohan’s personal memories with these long-forgotten news recordings; two formats that couldn’t be more different, yet somehow fit… And that unique combination is the format we’re exploring today!

Hello!👋 A quick note: This dispatch breaks from the usual format. Instead of deconstructing one example with repeatable steps, I’m following a single thread: what happens when formats collide.

If you’re new here, welcome! This is a bit of a departure, but it’s a good introduction to how I think about learning design. Feel free to explore the archive to see how I usually do things.

Back to regular programming next dispatch! :)

📰 What’s the format?

LS83 is a documentary by Herman Szwarcbart built from two distinct formats:

Format 1: Intimate, wandering childhood memories (Martín Kohan’s first-person narration)

Format 2: Public, news broadcasts (Channel 9 archival footage)

Through Martín’s first-person narration, we step into his world: kids trading stickers, sharing afternoon snacks, playing soccer, and getting into trouble. These memories unfold alongside the darker backdrop of a dictatorship in Argentina.

What’s interesting is that the filmmakers never tried to force alignment. Sometimes the formats echo each other, sometimes they collide, and other times they go their separate ways… And that’s deliberate:

[…] we made an initial selection and began experimenting, editing, testing, and playing with the overlap of both materials. From the start, we were clear that we didn’t want the images to literally illustrate the text, nor the text to serve as captions for the images. Herman Szwarcbart, Director

What captivated me about this documentary wasn’t what was happening on screen, but how the childhood memories intertwined with it. The collision of formats creates a third space, one where viewers actively make meaning by moving between intimate and historical, personal and political, trivial and relevant…

My cousin Jorge told me that, contrary to what one might assume, the sound of the engines could hardly be heard from inside the plane…

(Side note)

Martín Kohan’s book Me Acuerdo was inspired by the work of the French writer Georges Perec Je me souviens, a collection of 480 brief memories by the author which form a generational portrait of mid-20th-century France. Perec’s book, in turn, was inspired by the book I Remember from American writer Joe Brainard1.

(end of side note)

🎛️ Invisible architectures

Watching LS83 sent me down a rabbit hole. I wanted to understand why that collision of formats2 worked so well. Why combining personal memory with news footage created something neither format could achieve alone.

To understand why this works, I turned to musician David Byrne (whom I’m a huge fan of). In his book How Music Works, he writes that every creative act emerges from its context: the space, tools, and audience around it.

We unconsciously and instinctively make work to fit preexisting formats.

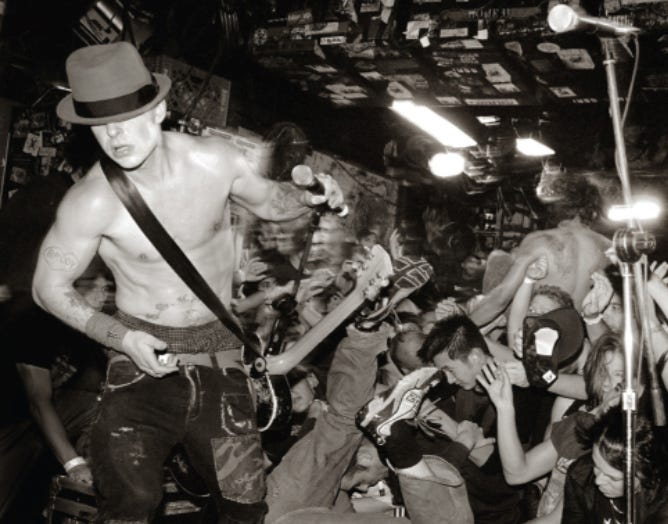

Byrne points out that West African drumming and chanting evolved outdoors, where rhythms had to carry across open distances. He contrasts this with how the cramped, sweaty New York clubs shaped the raw, fast sound of early punk bands.

“The tight space, cheap PA system, and proximity to the audience encouraged short songs, simple setups, and raw energy…”

In a sense, the space, the platform, and the software “makes” the painting, the playground, or the song…

Byrne emphasizes that once recording became central, the studio itself became the context. Musicians started making music that couldn’t even exist live (think of multi-track layering or reverb effects). He cites Brian Eno’s ambient works and some Talking Heads albums, where they wrote songs in the studio by looping rhythms, building textures, and reacting to what the technology allowed.

The tape machine, the mixing board, and later digital software became the “room” the music was made for.

Architecture, technology, audience behavior, and available tools all act like invisible co-authors of a format, shaping what kinds of art feel possible or natural. The room, in a way, writes the song.

And formats are those rooms! They are the invisible architectures of creativity.

And here’s what LS83 made me realize: What if you deliberately design for multiple rooms?

Szwarcbart chose two formats with incompatible logics and put them in conversation. The news archive “room” has its own rules: objective, authoritative, focused on public events. The memory “room” has completely different rules: subjective, meandering, focused on trivial, personal details…

The magic is in the collision. Neither room dominates. Viewers have to hold both simultaneously, and that tension creates a richer understanding than either format could provide alone.

We lived on the ground floor, facing the street.

Upstairs, there was a German woman named Carlota.

One day, she threw a bucket of water down at us from her balcony because we were playing ball and shouting…

💡 Formats that expand thinking

This reminds me of an essay by Michael Nielsen, who explores designing ‘media for thought’. Not just ways to transmit information, but formats that expand the range of thoughts humans can have.

In his essay Reinventing Explanation, Nielsen writes that the right medium can reshape intuition and reduce cognitive load, making possible certain kinds of understanding that weren’t before. He argues that the medium we use to explain something can reshape how we think about it.

LS83 does this. By forcing you to navigate between memory and archive, it makes you think differently about history. You can’t just absorb facts or empathize with memories, you have to hold both at once, feel the gaps and overlaps, construct your own understanding of how different things are entangled. This medium changes what’s cognitively possible for the viewer…

🌀 Collisions in Learning Design

So what does this mean for learning design?

Most learning experiences stick to one format: a lecture, a discussion, a hands-on activity, a game… And like Byrne showed us, each format has its own logic that shapes what’s possible. In learning, too, the “room” matters (after all, the container is a threshold). An interactive book feels deeply intimate and personal. A scavenger hunt turns the world into the classroom. An antidisciplinarathon invites you to create something with a stranger. A tiny desk concert encourages you to work with constraints. Each format invites a different kind of participation...

But what if we designed for collision? What if we deliberately combined formats with incompatible logics, the way LS83 does?

This is what great learning experiences should do. Not just deliver content in a clever package, but create unexpected collisions between formats that generate new ways of thinking (and creating)…

🎬 Ecosystems, not just formats

From How Music Works, I learned that context is the whole ecosystem that shapes creation: the physical space, the tools, the audience, and even the culture. A format zooms in on the structure that emerges from that context. A format is the frame.

From LS83, I learned that the most powerful formats are actually ecosystems, multiple rooms in deliberate conversation.

The reason this matters is that the right ecosystem can change and expand the range of thoughts humans can have and what they can create.

Byrne is right: the room writes the song. Nielsen is also right: the proper medium can expand the range of thoughts we can have.

And with LS83, Szwarcbart shows us we can design for multiple rooms and mediums at once. When you have to navigate between incompatible formats, you’re developing the ability to hold multiple logics at once.

🗒️ Three formats that create collisions

Here are a few examples of formats that "shouldn’t work together” creating a third space (a learning ecosystem):

Format 1: Trading card game (fantasy logic, fictional powers, competitive collection, game mechanics)

Format 2: Community directory/intergenerational mentorship (real people, lived expertise, social connection, storytelling)

Neither format alone could achieve this result: pure mentorship feels like obligation, pure card games stay fictional. Together, they create a third space where learning happens through play.

Format 1: Book (static, spatial, self-paced, silent, you control the navigation)

Format 2: Audio performance/guided experience (temporal, linear, paced by narrator, sonic, someone else controls the navigation)

You’re simultaneously reader and participant. You’re both in control (holding the book) and not in control (following instructions). You’re experiencing linearity (audio) and non-linearity (jumping pages) at once. You’re alone (with headphones) and accompanied (by the narrator)…

Format 1: Film screening (passive viewing, you sit in darkness, consume a narrative, it’s about other people’s lives…)

Format 2: Interactive experience (active participation, you’re in a social space, you create your own, personal narrative)

A film asks you to watch others, an interactive experience asks you to examine yourself. Film is consumption, the experience that follows is creation. Film keeps you at distance, this experience demands vulnerability. A film tells a story, the experience asks you to write your own…

I looked in the phone book for the addresses of Boca players.

I found Pancho Sa’s.

It was in Belgrano.

I rode my bike to his house, sat by the door to wait for him, and saw him walk in when he arrived…

When the lights came up at the theater in Buenos Aires, the director joined the stage for a Q&A.

I asked him what had surprised him most while making the film.

He spoke about the serendipity of discovering Martín’s memories just when he needed them most. Specially because he had already read Joe Brainard and Georges Perec. But Kohan’s book struck closer to home: they were almost the same age and raised in middle-class families in Buenos Aires.

The memories gave him a second format to collide with the first, and suddenly, the film came alive…

💌 An invitation

Formats are interesting to explore, but the most exciting discoveries lie in ecosystems, in combinations, in remixes, like the one in LS83.

What “room” shapes the work you create? Where in your work could two formats that weren’t meant to meet collide to create something new? If you redesigned your format from the inside out, what new behaviors or conversations might emerge?

🪁 Life Lately

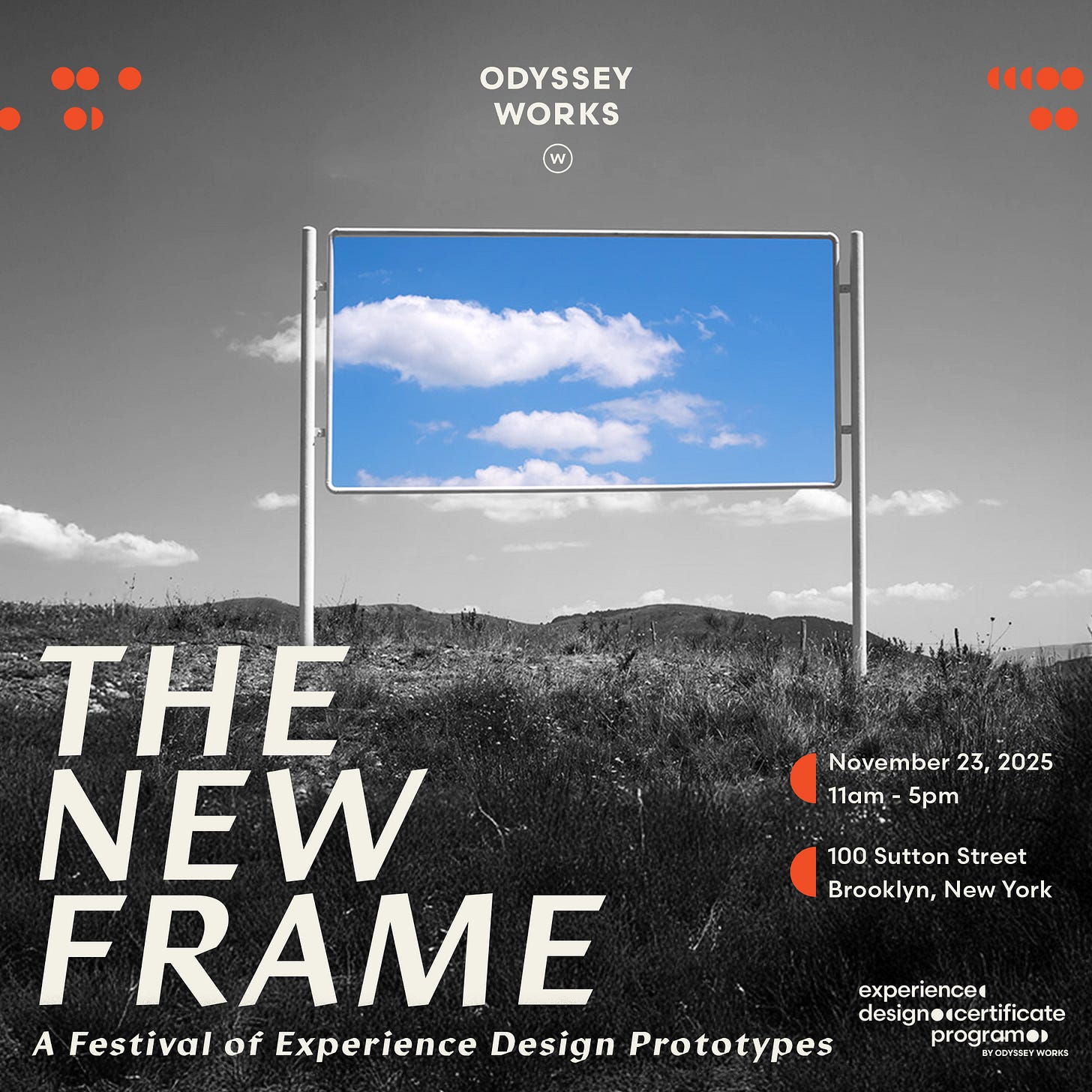

Speaking of formats and frames, next week, Robyn and I will be presenting our Museum in a Suitcase in The New Frame, a Festival of Experience Design Prototypes in Brooklyn, NY. If you’re around, stop by and say hi! (You can get your ticket here).

I had a lot of fun designing the latest learning experience for the 100 School where we teach how to explore AI with curiosity and creativity. I’m going to be writing more about it soon! A big highlight was working with

, a developer who ALSO knows a lot about education (you don’t find that special combo very often…)After being a fan of her work for more than 10 years, I had a zoom call with

!! I spent the rest of the day absolutely awestruck. I recommend this recent talk she gave: AI Is Our Multiple-Choice Test.

I appreciate your time. Thank you for reading! 💙 I also value your feedback (suggestions, critiques, constructive ideas…) I’d love to hear about you in the comments.

→ Or just click the heart symbol. That always makes me smile :-)

Another side note (that could potentially become a rabbit hole):

Perec was part of a group called OuLiPo (short for Ouvroir de littérature potentielle) which roughly translates to Workshop of Potential Literature. It was a literary experiment founded in 1960 by a mix of French-speaking writers and mathematicians who wanted to see what would happen when you applied rules and limits to writing. They borrowed ideas from math. Things like constraints, patterns, combinations, even algorithms and fractals, and used them as creative tools to play with language.

Originally, format referred quite literally to physical shape or layout: the size of a page. Once printing arrived, it began to mean a system for arranging content within a frame. By the 1800s, it was already about structure that enables expression (from the Latin formare: “to shape or to form”).

When computers came along, they borrowed the term directly from publishing. A file format became the container and convention that define how data is stored, read, and interpreted.

So whether in books or bytes, a format is the architecture of expression: the invisible structure that makes creation legible.

*This post’s cover gif is from @alcrego

Me encantó! Me dejó pensando en cómo los jardines digitales pueden ser ecosistemas de aprendizaje ❤️