No. 10 — Miracles, mechanical monks, and moving machines

Or how play could be another measure for human progress

A mechanical miracle

The year was 1562 and the incident was a national calamity. The crown prince of Spain, age 17, was walking down a flight of stairs when he tripped, fell, and bashed his head against a door near the bottom of the stairs. He grew delirious, burning with fever, and even lost his sight…

The prince’s father, King Phillip II, was at the time the most powerful man in the world. He called the best doctors in Europe to help his son but nothing could be done. The prince was basically on his death bed. Legend goes that the King kneeled beside his son and made a pact with God. “If you help me, if you heal my son, if you do this miracle for me, I'll do a miracle for you”.

That night, and this is well documented, the prince recounts having had a dream. A monk entered the room, approached his death bed, and told the prince he was going to be fine. Based on the physical description of the monk, people were certain that it was Diego De Alcalá, a local Friar who died 100 years before.

All of a sudden, the prince just got better. In a matter of days, he recovered his sight, his wounds healed, and it was like if the accident had never happened.

Confronted with the promise he had made to God, King Phillip needed to craft a miracle. That’s when he decided to contact a renowned clock maker named Juanelo Turriano and asked him to build a “mechanical version of Diego de Acalá”. A mechanical monk, if you will.

The automaton, now over 400 years old, is painted in human likeness. The monk figure walks slowly and steadily. He beats his chest in penitence and regularly lifts his left hand toward his lips. The head turns from right to left, the eyes roll in the head, and the mouth opens and closes as if it's sort of muttering a prayer…

Why an automaton and not a church, a sculpture or a crusade? The answer is unknown, but the King’s decision might explain human’s fascination with toy-like, moving machines…

From clockworks to automata

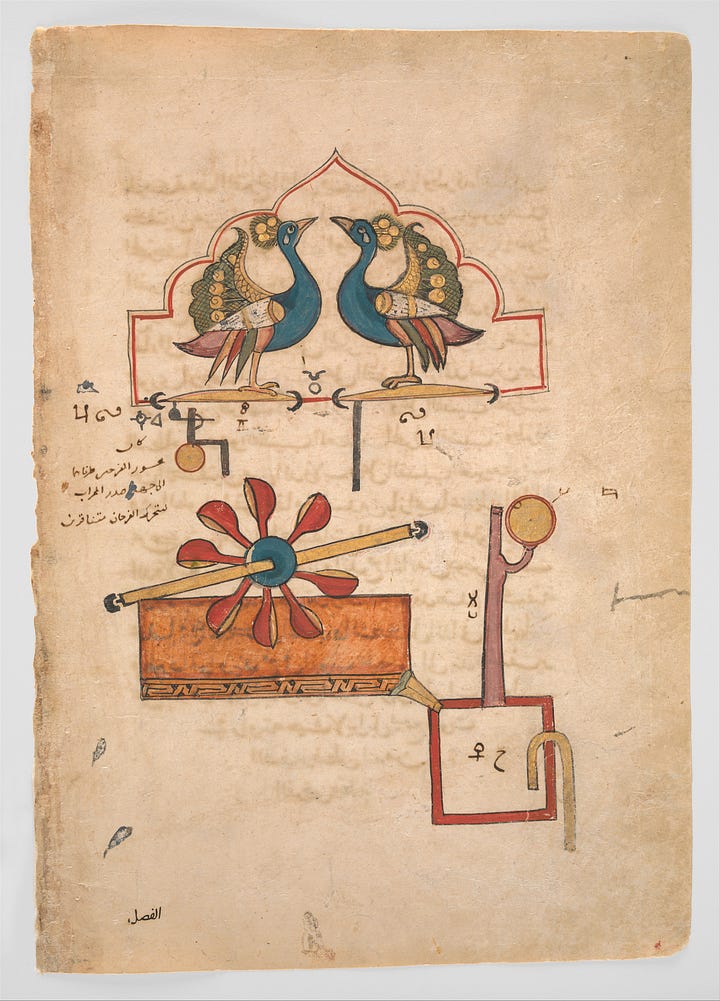

Automata have captivated the human imagination since ancient times. The roots of this fascination can be traced back to ancient Greece. As legends tell, King Solomon owned a throne protected by roaring mechanical beasts that came to life as someone drew near. In the ninth century, the Persian alchemist Jabir ibn Hayyan crafted statues that could move. Stories also speak of an extraordinary mechanical man who entertained King Mu of Zhou in tenth-century China. Even the Ottomans contributed to this marvel, crafting birds that could sing.

Automata became more common in the 1600 as inventions that evolved out of mechanical clocks. By the end of the seventeenth century, the clocks blossomed into miniature stage shows, called clockworks, that presented simple narratives using the mechanized movements of hundreds of little elements.

In 1772, Pierre Jaquet-Droz, who also made clocks, built the Writer, a mechanical boy composed of more than 6,000 parts, seated on a stool with a quill pen in hand. The boy could be programmed to write any combination of words using up to forty characters. A big milestone in the history of programmable machines.

In 1776, a Swiss inventor and showman with the name of John-Joseph Merlin was running an eclectic establishment known as Merlin’s Mechanical Museum. A hybrid between a science museum, a gaming arcade, and a maker lab, here you could find mechanical dolls, gambling machines, and music boxes. Merlin, another clockmaker by trade, was always intrigued by the possibilities of machines that could mimic physical behavior, so he began making and collecting automatons himself.

In the attic above the Museum, Merlin kept two miniature female automata, no more than a foot or two tall. One of them was a dancer whose arms moved with grace and who held in her hand a bird that could wag its tail and flap its wings. She was called the Silver Lady.

Automata were playthings, merely novelties… but through that play, a larger and more revolutionary idea was slowly taking place.

From automata to the first programmable computer

In 1801, a mother brought her eight-year-old son to visit Merlin’s Museum. His name was Charles Babbage. Merlin offered to take the boy to the attic workshop where he kept his mechanical dolls. The boy was amazed and he grew fascinated thinking about ways that machines can perform human tasks. Many years later, he discovered the Silver Lady at a bankruptcy auction and bought it.

In 1810, Babbage started to study Mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge. He then became Lucasian professor of Mathematics in the University of Cambridge, the chair held previously by Newton and later by Hawking.

Almost thirty years after his visit to Merlin’s attic, Babbage published On the Economy of Machinery and Manufacturers. He also began sketching plans for a calculating machine he called the Difference Engine, an invention that would eventually lead him to the Analytical Engine several years later, now considered to be the first programmable computer ever imagined.

Few people, however, saw the beauty of Babbage’s proposed machine, but he did find one believer (who’s also one of the people I admire the most): Ada Lovelace.

Walter Isaacson wrote in The Innovators that Ada’s love for both poetry and math primed her to see beauty in a computing machine. She was an examplar of the era of Romantic science, which was characterized by an enthusiasm for invention and discovery. “It was a period driven by a common ideal of intense, even reckless personal commitment to discovery”, wrote Richard Holmes in The Age of Wonder.

According to Babbage’s own account, the passion for mechanical thinking that led to the Difference Engine began with that moment of discovery in Merlin’s attic.

Exploring the margins of play

Automata weren't just mere toys. They often foreshadowed significant advancements yet to come, acting as signals of future developments. This prophetic effect becomes evident when we examine the discussions that surrounded the remarkable automata of the 18th century. These creations influenced Marx's theories on labor; they fueled Babbage's visionary concept of mechanized intelligence, and they even sowed the seed for Mary Shelley's iconic work: Frankenstein. In both their mechanical design and their philosophical implications, the automata were ahead of their time.

Sometimes “insignificant inventions” are the bedrock for bigger inventions. And even though political events, religions, and the kinds of things that are typically written in History books can tell you quite a bit about the current state of the social order, trivial discoveries, curiosities, and the things we play, can be great signals of what’s coming next…

So when was the last time you played?

When I was a kid, I spent hours trying to build a treehouse without worrying about whether I was wasting my time, or how my treehouse was compared to the neighbor’s, or if it fulfilled all the requirements of the best treehouses on the block. Just building something for the sake of it, for the sake of having fun, was enough. These days, whenever I start to build something new I worry of plenty of things: will people want this? Is it easy and intuitive? Is it functional? Is it similar to other things that already exist? Am I wasting my time?

When I think of it, there’s nothing really stopping me from working on projects just for fun. Wait. On second thought, maybe there are two things: 1) An internal voice telling me that I’m not being productive; and 2) an internal voice telling me that this is stupid. But when I think of the treehouse, I’m reminded of that careless confidence that I had every time I was starting something new. It was exciting, it felt like something full of possibilities, it was simply fun.

Maybe the most important part of starting a project is that: just starting. And having high standards of productivity or of what others might think of what you build (Did you really build a Silver Lady with a bird that sings?), can be a huge detractor.

Things can have meaning even if they don’t lead to something else. As adults it’s also worth exploring the margins of play.

What if we gave ourselves a chance to an intense, even reckless personal commitment to discovery?

This was lovely! Thank you!