Learning spaces with corner stoops

How urban design can help us rethink learning environments

In the 1950s, Jane Jacobs was walking the streets of Greenwich Village with a notebook in hand, observing what made a city feel alive. She wrote about corner shops, stoops, kids playing on sidewalks… details that city planners often ignored.

Just a few miles away, Joan Ganz Cooney had recently moved from Arizona to Manhattan. She was in her twenties, working in television, and starting to imagine how media could serve children who had been left out of traditional classrooms.

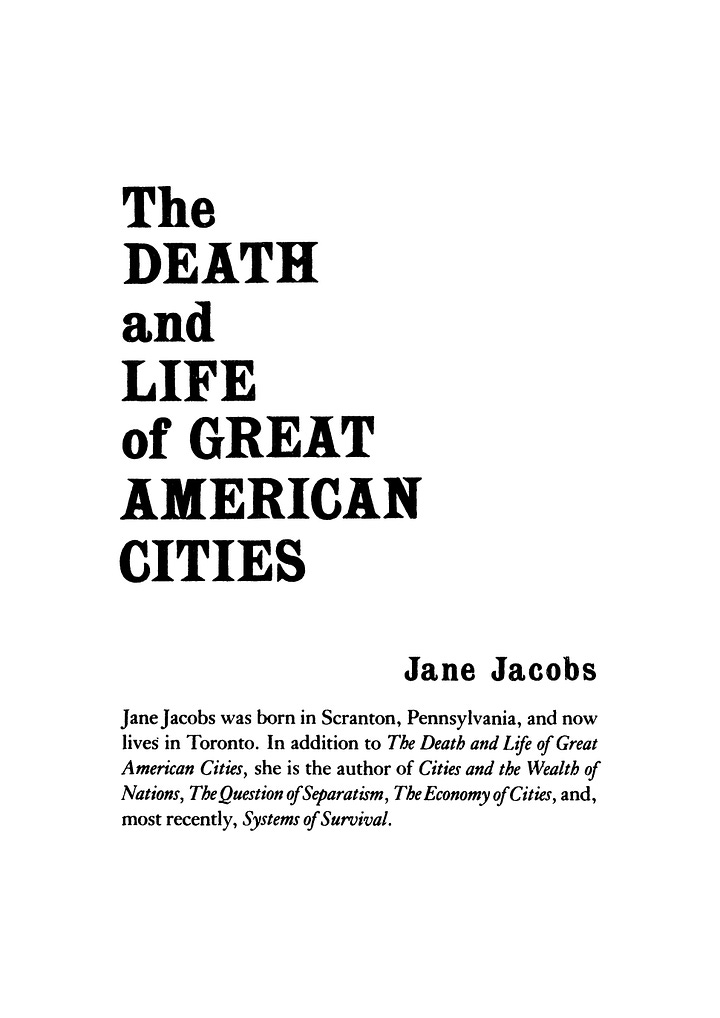

By the 1960s, Jacobs was challenging the orthodoxy of urban planning with The Death and Life of Great American Cities, while Cooney was laying the groundwork for Sesame Street. Jane was doing activism against Robert Moses' expressways. Meanwhile, Joan was writing her famous report on educational TV.

Jane’s and Joan’s work didn’t overlap directly, but it came from the same place and from the same belief: that real community and real learning happen in everyday spaces. And that’s the format we’re exploring today.

📰 What’s the format?

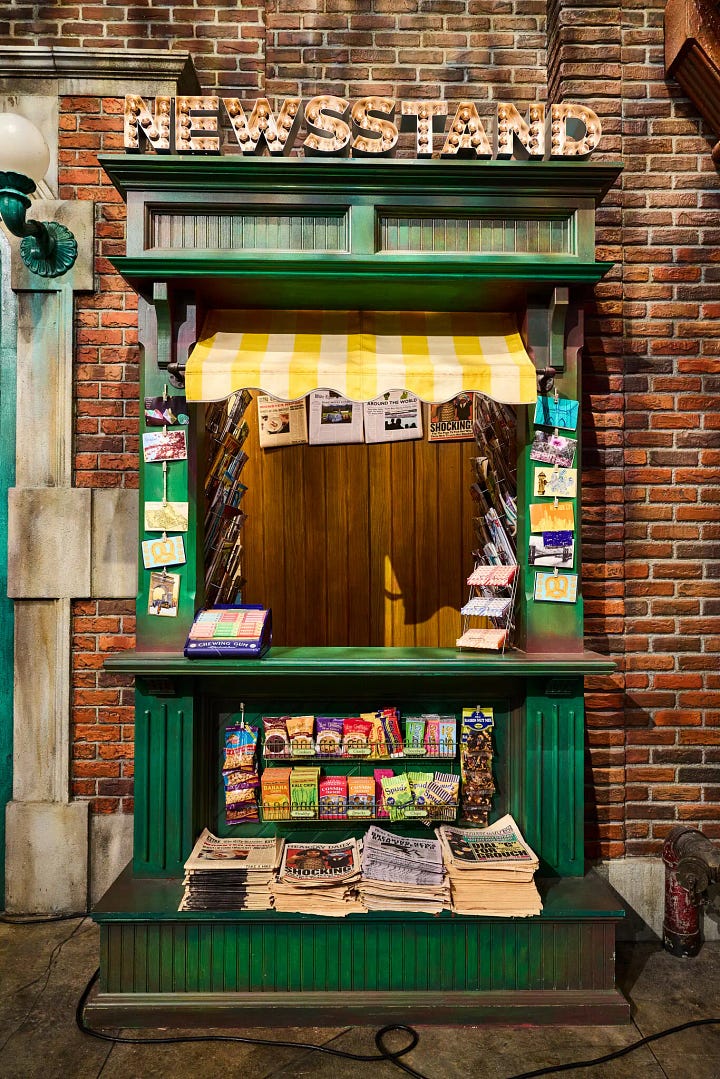

I learned of this overlap between a city urbanist who wasn’t a planner, and a TV producer who became a teacher after reading this article about Sesame Street. It described the show’s set as one of the most recognizable blocks in the world, lasting, in part, because it’s both realistic and idealistic.

What if learning spaces followed that same duality? Maybe learning spaces, like neighborhoods, should be grounded in reality but also point to more ambitious, out-of-the-box possibilities. How might that look?

🎛️ What are the features?

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities Jane Jacobs outlined four principles she thought were indispensable to a flourishing neighborhood:

It should serve multiple functions

Blocks should be short

Buildings should “vary in age and condition”

There should be a “dense concentration of people.”

Now picture Sesame Street:

A mix of shops, apartments, and community spaces

A stoop where people gather

People of different ages, races, and roles interacting

Lots of unscripted, everyday life: kids playing, neighbors chatting, surprises happening…

Since reading that article, the question I keep coming back to is this: What are the learning equivalents of short blocks, mixed use, and corner stoops? What kind of structure encourages curiosity, interaction, and discovery?

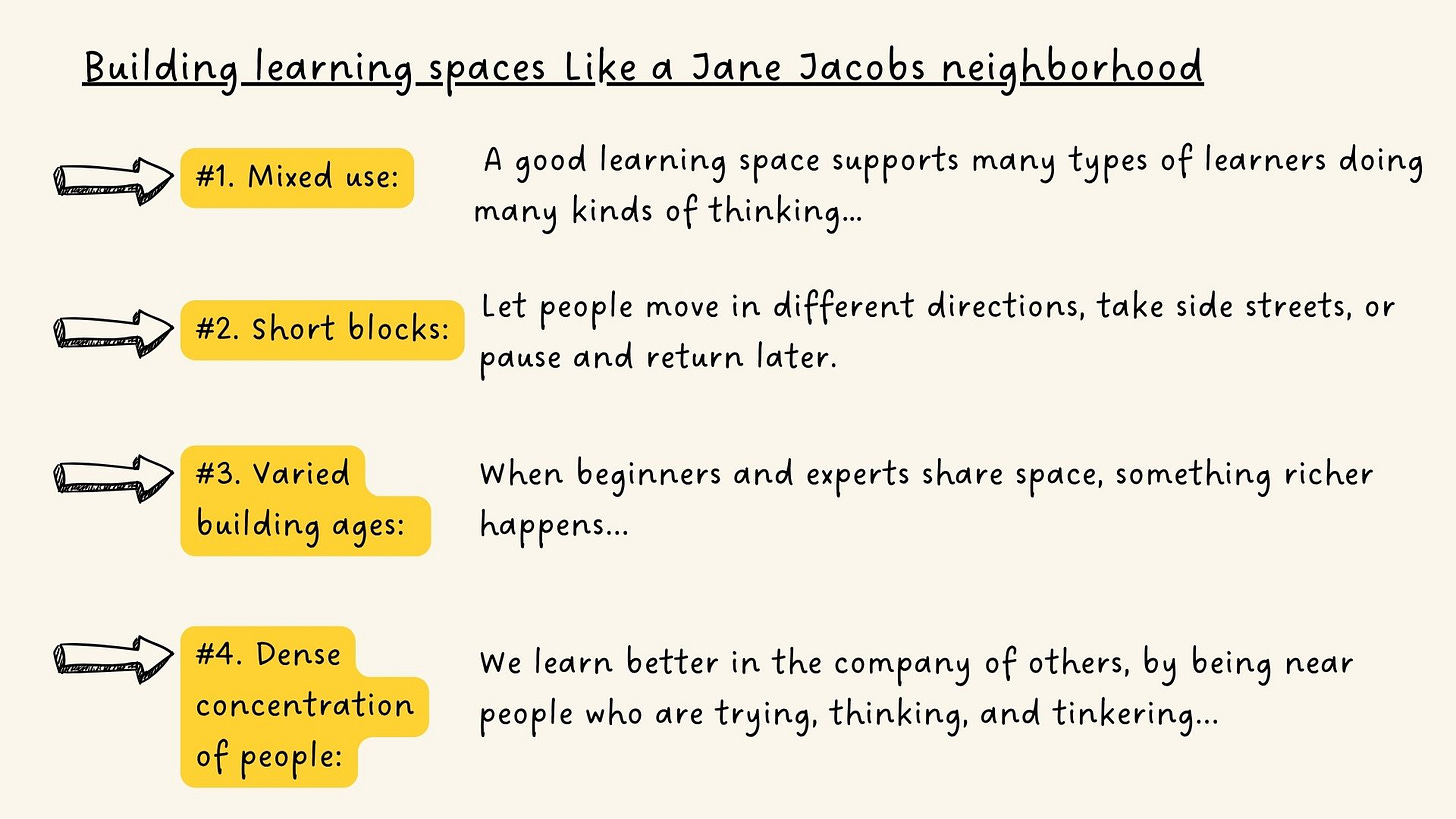

💡 Urban design principles for learning spaces

Jane Jacobs wasn’t writing about learning, but her principles for vibrant neighborhoods might offer some insights into what makes good learning environments.

#1. Mixed use

Jacobs believed streets should serve many purposes: living, working, playing, gathering. The more uses, the more life.

A good learning space supports many types of learners doing many kinds of thinking…

#2. Short blocks

Short blocks create more corners, more movement, more chances to connect.

In learning, short blocks could translate into flexible paths. Let people move in different directions, take side streets, or pause and return later. This increases the surface area for learning: more chances to connect with others, share work and stumble onto something unexpected.

#3. Varied building ages

Jacobs valued older buildings because they made room for experimentation. They were flexible, affordable, and open to first tries.

In learning, we often group people by level, but when beginners and experts share space, something richer happens. Newcomers learn by observing, while experienced learners sharpen their thinking by explaining and adapting.

#4. Dense concentration of people

Jacobs loved density not for its size, but for its potential: people bump into each other, share stories, watch, copy, chat...

Learning is no different. We learn better in the company of others. Not always through direct instruction, but by being near people who are trying, thinking, stumbling and figuring things out.

💌 An invitation

Just like Sesame Street, the best learning spaces live at the intersection of the realistic and the idealistic; grounded in everyday life, but designed to stretch our imagination of what’s possible.

What would it look like to design your learning spaces the way Jacobs imagined neighborhoods? Layered, lived-in, full of movement and chance encounters? Where could you make room for more paths, more overlap, more exchange between levels of experience?

We often try to tidy learning up, when maybe what it needs is a bit more texture. What might you try shifting in your own space?

🪁 Life Lately

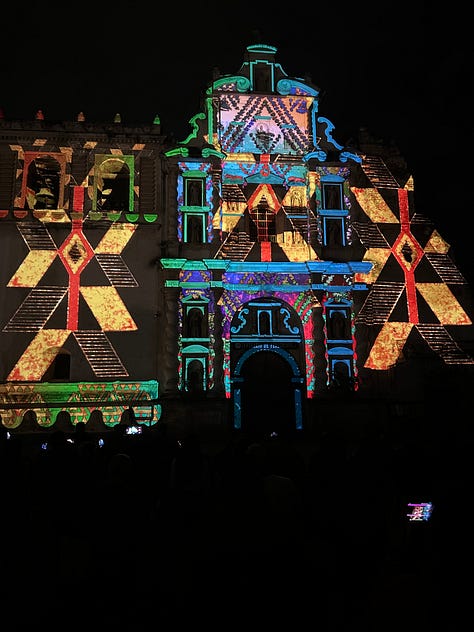

Went to a videomapping festival in Antigua, inspired on the magical realism movement (Miguel Ángel Asturias, Gabriel García Márquez, Juan Rulfo…)

Created a scavenger hunt for my 3-year old niece

Watched the short film Ten Meter Tower by Maximilien Van Aertryck and Axel Danielson, where they coaxed dozens of people to jump off of a 10-meter diving platform for the first time. It’s a great representation of how we struggle with ourselves, trying to overcome our fears… I couldn’t stop watching.

I appreciate your time. Thank you for reading! 💙 I also value your feedback (suggestions, critiques, constructive ideas…) as well as your tips or suggestions for future editions. I’d love to hear about you in the comments.

→ Or just click the heart symbol. That always makes me smile :-)

*This post’s cover gif is from McGill University